18 KiB

ADR 056: Light client amnesia attacks

Changelog

- 02.04.20: Initial Draft

- 06.04.20: Second Draft

- 10.06.20: Post Implementation Revision

- 19.08.20: Short Term Amnesia Alteration

- 01.10.20: Status of Amnesia for 0.34

Context

Whilst most created evidence of malicious behavior is self evident such that any individual can verify them independently there are types of evidence, known collectively as global evidence, that require further collaboration from the network in order to accumulate enough information to create evidence that is individually verifiable and can therefore be processed through consensus. Fork Accountability has been coined to describe the entire process of detection, proving and punishing of malicious behavior. This ADR addresses specifically what a light client amnesia attack is and how it can be proven and the current decision around handling light client amnesia attacks. For information on evidence handling by the light client, it is recommended to read ADR 47.

Amnesia Attack

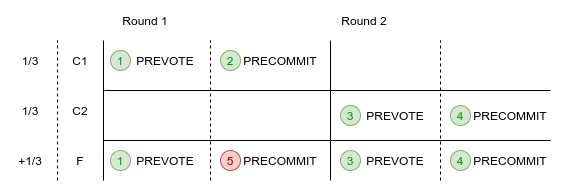

The schematic below explains a scenario where an amnesia attack can occur such that two sets of honest nodes, C1 and C2, commit different blocks.

- C1 and F send PREVOTE messages for block A.

- C1 sends PRECOMMIT for round 1 for block A.

- A new round is started, C2 and F send PREVOTE messages for a different block B.

- C2 and F then send PRECOMMIT messages for block B.

- F later on creates PRECOMMITS for block A and combines it with those from C1 to form a block

This forged block can then be used to fool light clients trying to verify it. It must be stressed that there are a few more hurdles or dimensions to the attack to consider.For a more detailed walkthrough refer to Appendix A.

Decision

The decision surrounding amnesia attacks has both a short term and long term component. In the long term, a more sturdy protocol will need to be fleshed out and implemented. There is already draft documents outlining what such a protocol would look like and the resources it would require (see references). Prior revisions however outlined a protocol which had been implemented (See Appendix B). It was agreed that it still required greater consideration and review given it's importance. It was therefore discussed, with the limited time frame set before 0.34, whether the protocol should be completely removed or if there should remain some logic in handling the aforementioned scenarios.

The latter of the two options meant storing a record of all votes in any height with which there was more than one round. This information would then be accessible for applications if they wanted to perform some off-chain verification and punishment.

In summary, this seemed like too much to ask of the application to implement only on a temporary basis, whilst not having the domain specific knowledge and considering such a difficult and unlikely attack. Therefore the short term decision is to identify when the attack has occurred and implement the detector algorithm highlighted in ADR 47 but to not implement any accountability protocol that would identify malicious validators and allow applications to punish them. This will hopefully change in the long term with the focus on eventually reaching a concrete and secure protocol with identifying and dealing with these attacks.

Implications

- Light clients will still be able to detect amnesia attacks so long as the assumption of having at least one correct witness holds

- Light clients will gossip the attack to witnesses and halt thus failing to validate the incorrect block (and therefore not being fooled)

- Validators will propose and commit evidence of the amnesia attack on chain

- No evidence will be passed to the application indicting any malicious validators, thus meaning that no malicious validators will be punished for performing the attack

- If a light clients bubble of providers are all faulty the light client will falsely validate amnesia attacks as well as any other 1/3+ light client attack.

Status

Implemented

Consequences

Positive

Light clients are still able to prevent falsely validating a block.

Already implemented.

Negative

Light clients where all witnesses are faulty can be subject to an amnesia attack and verify a forged block that is not part of the chain.

Neutral

References

Appendix A: Detailed Walkthrough of Performing a Light Client Amnesia Attack

As the attacker, a prerequisite to this attack is first to observe or attempt to craft a block where a subset (less than ⅓) of correct validators sent precommit votes for a proposal in an earlier round and later received ⅔ prevotes for a different proposal thus changing their lock and correctly sending precommit votes (and later committing) for the proposal in the latter round. The second prerequisite is to have at least ⅓ validating power in that height (or enough voting power to have ⅔+ when combined with the precommits of the earlier round).

To go back to how one may craft such a block, we begin with one of the validators in this cabal being the proposer. They propose a block with all the txs that they want to fool a light client with. The proposer then only relays this to the members of their cabal and a controlled subset of correct validators (less than ⅓). We will call ourselves f for faulty and c1 for this correct subset.

Attackers need to rely on the assistance of some form of a network partition or on the nature of the sporadic voting to conjure their desired environment. The attackers need at least ⅓ of the validating power of the remaining correct validators, we shall denote this as c2, to not see ⅔ prevotes and thus not be locked on a block when it comes to the next round. If we have less than ⅓ remaining validators that don’t see this first proposal, then we will not have enough voting power to reach ⅔+ prevotes (the sum of f and c2) in the following round and thus change the lock of c1 such that we correctly commit the block in the latter round yet have enough precommits in the earlier round to fool the light client. Remember this is our desired scenario: to save all these precommit votes for a different (in this case earlier) proposed block.

To try to break this down even further let’s go back to the first round. F sends c1 a proposal (and not c2), c1 in turn sends their prevotes to all whom they are connected to. This means that some will be received by c2. F then sends their prevotes just to c1. Now not all validators in c1 may be connected to each other, so perhaps some validators in c1 might not receive ⅔ (from their own cohort and from f) and thus not precommit. In other situations we may see a validator in c2 connected to all validators in c1. Therefore they too will receive ⅔ prevotes and thus precommit. We can conclude therefore that although targeting this c1 subset of validators, those that actually precommit may be somewhat different. The key is for the attackers to observe the n amount of precommits they need in round 1 where n is ⅔+ - f, whilst ensuring that n itself does not go over ⅓. If it does then less than ⅔ validators remain to be able to change the lock and commit the block in the later round.

An extra dimension to this puzzle is the timeouts. Whilst c1 is relaying votes to its peers and these validators count closer towards the ⅔ threshold needed to send their precommit votes at any moment the timeout could be reached and thus the nodes will precommit nil and ignore any late prevote messages.

This is all to say that such an attack is partly out of the attackers hands. All they can do is tweak the subset of validators that they first choose to gossip the proposal and modify the timings around when they send their prevotes until they reach the desired precondition: n precommits for an earlier proposal and ⅔ precommits for the later proposal. So this is up to the gods of non deterministic behavior to help them out with their plight. I’m not going to allocate the hours to calculate the probability but it could be in the magnitude of 1000’s of blocks trying to get this scenario before the precondition is met.

Obviously, the probability becomes substantially higher as the cabal’s voting power nears ⅔. This is because both n decreases and there is greater tolerance to send prevotes to a greater amount of validators without going overboard and reaching the ⅓ precommit threshold in the first round which would mean they would have to try again.

Once we’ve got our n, we can then forge the remaining signatures for that block (from the f) and bundle them all together and tada we have a forged signed header.

Now we’ve done that, it’s time to find some light clients to fool.

Also critical to this type of attack is that the light client that is connected to our nodes must request a light block at that specific height with which we forged this signed header but this shouldn’t be hard to do. To bring this back to a real context, say our faulty cabal, f, bought some groceries using atoms and then wanted to prove that they did, the grocery owner whips out their phone, runs the light client and f tells them the height they committed the transaction.

An important note here is that because the validator sets are the same between the canonical and the forged block, this attack also works on light clients that verify sequentially. In fact, they are especially vulnerable because they currently don’t run the detector function afterwards.

However, if our grocery owner verifies using the skipping algorithm, they will then run the detector and therefore they will compare with other witness nodes. Ideally for our attackers, if f has a lot of nodes exposing their rpc endpoints, then there is a chance that all the witnesses the light client has are faulty and thus we have a successful attack and the grocery owner has been fooled into handing f a few apples and carrots.

However, there is a greater chance, especially if the light client is connected to quite a few other nodes that a divergence will be detected. The light client will figure out there was an amnesia attack and send the evidence to the witness to commit on chain. The grocery owner will see that verification failed and won't hand over the apples or carrots but also f won't be punished for their villainous behavior. This means that they can go over to the hairdressers and see if they can pull off the same stunt again.

So this brings to the fore the current defenses that are in place. As long as there has not been a cabal of validators with greater than 1/3 power (or the trust level), the light clients verification algorithm will prevent any attempts to deceive it. Greater than this threshold and we rely on the detector as a second layer of defense to pick up on any attack. It's security is chiefly tied with the assumption that at least one of the witnesses is correct. If this fails then as illustrated above, the light client can be suceptible to amnesia (as well as equivocation and lunatic) attacks.

The outstanding problem, if we indeed consider it big enough to be one, therefore lies in the incentivisation mechanism which is how f and other malicious validators are punished. This is decided by the application but it's up to Tendermint to identify them. With other forms of attacks the evidence lies in the precommits. But because an amnesia attack uses precommits from another round, which is information that is discarded by the consensus engine once the block is committed, it is difficult to understand which validators were in fact faulty.

If we cast our minds back to what I previously wrote, part of an amnesia attack depends on getting n precommits from an earlier round. These are then bundled with the malicious validators' own signatures. This means that the light client nor full nodes are capable of distinguishing which of the signatures were correctly created as part of Tendermint consensus and which were forged later on.

Appendix B: Prior Amnesia Evidence Accountability Implementation

As the distinction between these two attacks (amnesia and back to the past) can only be distinguished by confirming with all validators (to see if it is a full fork or a light fork), for the purpose of simplicity, these attacks will be treated as the same.

Currently, the evidence reactor is used to simply broadcast and store evidence. The idea of creating a new reactor for the specific task of verifying these attacks was briefly discussed, but it is decided that the current evidence reactor will be extended.

The process begins with a light client receiving conflicting headers (in the future this could also be a full node during fast sync or state sync), which it sends to a full node to analyze. As part of evidence handling, this is extracted into potential amnesia evidence when the validator voted in more than one round for a different block.

type PotentialAmnesiaEvidence struct {

VoteA *types.Vote

VoteB *types.Vote

Heightstamp int64

}

NOTE: There had been an earlier notion towards batching evidence against the entire set of validators all together but this has given way to individual processing predominantly to maintain consistency with the other forms of evidence. A more extensive breakdown can be found here

The evidence will contain the precommit votes for a validator that voted for both rounds. If the validator voted in more than two rounds, then they will have multiple PotentialAmnesiaEvidence against them hence it is possible that there is multiple evidence for a validator in a single height but not for a single round. The votes should be all valid and the height and time that the infringement was made should be within:

MaxEvidenceAge - ProofTrialPeriod

This trial period will be discussed later.

Returning to the event of an amnesia attack, if we were to examine the behavior of the honest nodes, C1 and C2, in the schematic, C2 will not PRECOMMIT an earlier round, but it is likely, if a node in C1 were to receive +2/3 PREVOTE's or PRECOMMIT's for a higher round, that it would remove the lock and PREVOTE and PRECOMMIT for the later round. Therefore, unfortunately it is not a case of simply punishing all nodes that have double voted in the PotentialAmnesiaEvidence.

Instead we use the Proof of Lock Change (PoLC) referred to in the consensus spec. When an honest node votes again for a different block in a later round

(which will only occur in very rare cases), it will generate the PoLC and store it in the evidence reactor for a time equal to the MaxEvidenceAge

type ProofOfLockChange struct {

Votes []*types.Vote

PubKey crypto.PubKey

}

This can be either evidence of +2/3 PREVOTES or PRECOMMITS (either warrants the honest node the right to vote) and is valid, among other checks, so long as the PRECOMMIT vote of the node in V2 came after all the votes in the ProofOfLockChange i.e. it received +2/3 votes for a block and then voted for that block thereafter (F is unable to prove this).

In the event that an honest node receives PotentialAmnesiaEvidence it will first ValidateBasic() and Verify() it and then will check if it is among the suspected nodes in the evidence. If so, it will retrieve the ProofOfLockChange and combine it with PotentialAmensiaEvidence to form AmensiaEvidence. All honest nodes that are part of the indicted group will have a time, measured in blocks, equal to ProofTrialPeriod, the aforementioned evidence paramter, to gossip their AmnesiaEvidence with their ProofOfLockChange

type AmnesiaEvidence struct {

*types.PotentialAmnesiaEvidence

Polc *types.ProofOfLockChange

}

If the node is not required to submit any proof than it will simply broadcast the PotentialAmnesiaEvidence, stamp the height that it received the evidence and begin to wait out the trial period. It will ignore other PotentialAmnesiaEvidence gossiped at the same height and round.

If a node receives AmnesiaEvidence that contains a valid ProofOfClockChange it will add it to the evidence store and replace any PotentialAmnesiaEvidence of the same height and round. At this stage, an amnesia evidence with polc, it is ready to be submitted to the chin. If a node receives AmnesiaEvidence with an empty polc it will ignore it as each honest node will conduct their own trial period to be sure that time was given for any other honest nodes to respond.

There can only be one AmnesiaEvidence and one PotentialAmneisaEvidence stored for each attack (i.e. for each height).

When, state.LastBlockHeight > PotentialAmnesiaEvidence.timestamp + ProofTrialPeriod, nodes will upgrade the corresponding PotentialAmnesiaEvidence and attach an empty ProofOfLockChange. Then honest validators of the current validator set can begin proposing the block that contains the AmnesiaEvidence.

NOTE: Even before the evidence is proposed and committed, the off-chain process of gossiping valid evidence could be enough for honest nodes to recognize the fork and halt.

Other validators will vote nil if:

- The Amnesia Evidence is not valid

- The Amensia Evidence is not within their own trial period i.e. too soon.

- They don't have the Amnesia Evidence and it is has an empty polc (each validator needs to run their own trial period of the evidence)

- Is of an AmnesiaEvidence that has already been committed to the chain.

Finally it is important to stress that the protocol of having a trial period addresses attacks where a validator voted again for a different block at a later round and time. In the event, however, that the validator voted for an earlier round after voting for a later round i.e. VoteA.Timestamp < VoteB.Timestamp && VoteA.Round > VoteB.Round then this action is inexcusable and can be punished immediately without the need of a trial period. In this case, PotentialAmnesiaEvidence will be instantly upgraded to AmnesiaEvidence.