5.8 KiB

Tendermint Architectural Overview

November 2019

Over the next few weeks, @brapse, @marbar3778 and I (@tessr) are having a series of meetings to go over the architecture of Tendermint Core. These are my notes from these meetings, which will either serve as an artifact for onboarding future engineers; or will provide the basis for such a document.

Communication

There are three forms of communication (e.g., requests, responses, connections) that can happen in Tendermint Core: internode communication, intranode communication, and client communication.

-

Internode communication: Happens between a node and other peers. This kind of communication happens over TCP or HTTP. More on this below.

-

Intranode communication: Happens within the node itself (i.e., between reactors or other components). These are typically function or method calls, or occasionally happen through an event bus.

-

Client communication: Happens between a client (like a wallet or a browser) and a node on the network.

Internode Communication

Internode communication can happen in two ways:

- TCP connections through the p2p package

- Most common form of internode communication

- Connections between nodes are persisted and shared across reactors, facilitated by the switch. (More on the switch below.)

- RPC over HTTP

- Reserved for short-lived, one-off requests

- Example: reactor-specific state, like height

- Also possible: web-sockets connected to channels for notifications (like new transactions)

P2P Business (the Switch, the PEX, and the Address Book)

When writing a p2p service, there are two primary responsibilities:

- Routing: Who gets which messages?

- Peer management: Who can you talk to? What is their state? And how can you do peer discovery?

The first responsibility is handled by the Switch:

- Responsible for routing connections between peers

- Notably only handles TCP connections; RPC/HTTP is separate

- Is a dependency for every reactor; all reactors expose a function

setSwitch - Holds onto channels (channels on the TCP connection--NOT Go channels) and uses them to route

- Is a global object, with a global namespace for messages

- Similar functionality to libp2p

TODO: More information (maybe) on the implementation of the Switch.

The second responsibility is handled by a combination of the PEX and the Address Book.

TODO: What is the PEX and the Address Book?

The Nature of TCP, and Introduction to the mconnection

Here are some relevant facts about TCP:

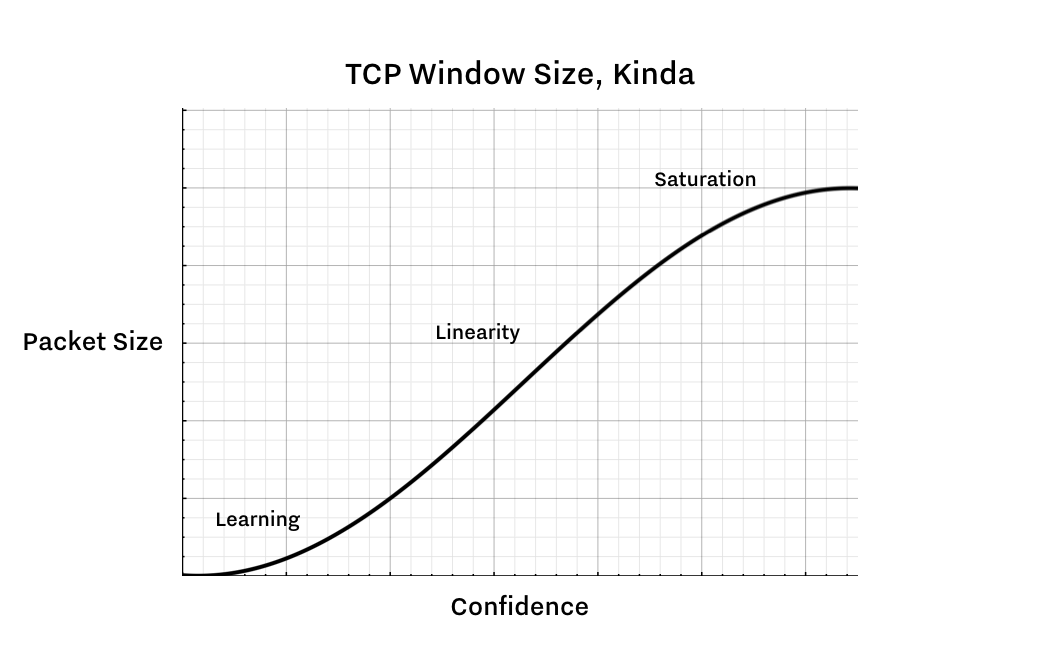

- All TCP connections have a "frame window size" which represents the packet size to the "confidence;" i.e., if you are sending packets along a new connection, you must start out with small packets. As the packets are received successfully, you can start to send larger and larger packets. (This curve is illustrated below.) This means that TCP connections are slow to spin up.

- The syn/ack process also means that there's a high overhead for small, frequent messages

- Sockets are represented by file descriptors.

In order to have performant TCP connections under the conditions created in Tendermint, we've created the mconnection, or the multiplexing connection. It is our own protocol built on top of TCP. It lets us reuse TCP connections to minimize overhead, and it keeps the window size high by sending auxiliary messages when necessary.

The mconnection is represented by a struct, which contains a batch of messages, read and write buffers, and a map of channel IDs to reactors. It communicates with TCP via file descriptors, which it can write to. There is one mconnection per peer connection.

The mconnection has two methods: send, which takes a raw handle to the socket and writes to it; and trySend, which writes to a different buffer. (TODO: which buffer?)

The mconnection is owned by a peer, which is owned (potentially with many other peers) by a (global) transport, which is owned by the (global) switch:

switch

transport

peer

mconnection

peer

mconnection

peer

mconnection

node.go

node.go is the entrypoint for running a node. It sets up reactors, sets up the switch, and registers all the RPC endpoints for a node.

Types of Nodes

- Validator Node:

- Full Node:

- Seed Node:

TODO: Flesh out the differences between the types of nodes and how they're configured.

Reactors

Here are some Reactor Facts:

- Every reactor holds a pointer to the global switch (set through

SetSwitch()) - The switch holds a pointer to every reactor (

addReactor()) - Every reactor gets set up in node.go (and if you are using custom reactors, this is where you specify that)

addReactoris called by the switch;addReactorcallssetSwitchfor that reactor- There's an assumption that all the reactors are added before

- Sometimes reactors talk to each other by fetching references to one another via the switch (which maintains a pointer to each reactor). Question: Can reactors talk to each other in any other way?

Furthermore, all reactors expose:

- A TCP channel

- A

receivemethod - An

addReactorcall

The receive method can be called many times by the mconnection. It has the same signature across all reactors.

The addReactor call does a for loop over all the channels on the reactor and creates a map of channel IDs->reactors. The switch holds onto this map, and passes it to the transport, a thin wrapper around TCP connections.

The following is an exhaustive (?) list of reactors:

- Blockchain Reactor

- Consensus Reactor

- Evidence Reactor

- Mempool Reactor

- PEX Reactor

Each of these will be discussed in more detail later.

Blockchain Reactor

The blockchain reactor has two responsibilities:

- Serve blocks at the request of peers

- TODO: learn about the second responsibility of the blockchain reactor