31 KiB

ADR 075: RPC Event Subscription Interface

Changelog

- 01-Mar-2022: Update long-polling interface (@creachadair).

- 10-Feb-2022: Updates to reflect implementation.

- 26-Jan-2022: Marked accepted.

- 22-Jan-2022: Updated and expanded (@creachadair).

- 20-Nov-2021: Initial draft (@creachadair).

Status

Accepted

Background & Context

For context, see RFC 006: Event Subscription.

The Tendermint RPC service permits clients to subscribe to the event stream generated by a consensus node. This allows clients to observe the state of the consensus network, including details of the consensus algorithm state machine, proposals, transaction delivery, and block completion. The application may also attach custom key-value attributes to events to expose application-specific details to clients.

The event subscription API in the RPC service currently comprises three methods:

-

subscribe: A request to subscribe to the events matching a specific query expression. Events can be filtered by their key-value attributes, including custom attributes provided by the application. -

unsubscribe: A request to cancel an existing subscription based on its query expression. -

unsubscribe_all: A request to cancel all existing subscriptions belonging to the client.

There are some important technical and UX issues with the current RPC event subscription API. The rest of this ADR outlines these problems in detail, and proposes a new API scheme intended to address them.

Issue 1: Persistent connections

To subscribe to a node's event stream, a client needs a persistent connection to the node. Unlike the other methods of the service, for which each call is serviced by a short-lived HTTP round trip, subscription delivers a continuous stream of events to the client by hijacking the HTTP channel for a websocket. The stream (and hence the HTTP request) persists until either the subscription is explicitly cancelled, or the connection is closed.

There are several problems with this API:

-

Expensive per-connection state: The server must maintain a substantial amount of state per subscriber client:

-

The current implementation uses a WebSocket for each active subscriber. The connection must be maintained even if there are no matching events for a given client.

The server can drop idle connections to save resources, but doing so terminates all subscriptions on those connections and forces those clients to re-connect, adding additional resource churn for the server.

-

In addition, the server maintains a separate buffer of undelivered events for each client. This is to reduce the dual risks that a client will miss events, and that a slow client could "push back" on the publisher, impeding the progress of consensus.

Because event traffic is quite bursty, queues can potentially take up a lot of memory. Moreover, each subscriber may have a different filter query, so the server winds up having to duplicate the same events among multiple subscriber queues. Not only does this add memory pressure, but it does so most at the worst possible time, i.e., when the server is already under load from high event traffic.

-

-

Operational access control is difficult: The server's websocket interface exposes all the RPC service endpoints, not only the subscription methods. This includes methods that allow callers to inject arbitrary transactions (

broadcast_tx_*) and evidence (broadcast_evidence) into the network, remove transactions (remove_tx), and request arbitrary amounts of chain state.Filtering requests to the GET endpoint is straightforward: A reverse proxy like nginx can easily filter methods by URL path. Filtering POST requests takes a bit more work, but can be managed with a filter program that speaks FastCGI and parses JSON-RPC request bodies.

Filtering the websocket interface requires a dedicated proxy implementation. Although nginx can reverse-proxy websockets, it does not support filtering websocket traffic via FastCGI. The operator would need to either implement a custom nginx extension module or build and run a standalone proxy that implements websocket and filters each session. Apart from the work, this also makes the system even more resource intensive, as well as introducing yet another connection that could potentially time out or stall on full buffers.

Even for the simple case of restricting access to only event subscription, there is no easy solution currently: Once a caller has access to the websocket endpoint, it has complete access to the RPC service.

Issue 2: Inconvenient client API

The subscription interface has some inconvenient features for the client as well as the server. These include:

-

Non-standard protocol: The RPC service is mostly JSON-RPC 2.0, but the subscription interface diverges from the standard.

In a standard JSON-RPC 2.0 call, the client initiates a request to the server with a unique ID, and the server concludes the call by sending a reply for that ID. The

subscribeimplementation, however, sends multiple responses to the client's request:-

The client sends

subscribewith some IDxand the desired query -

The server responds with ID

xand an empty confirmation response. -

The server then (repeatedly) sends event result responses with ID

x, one for each item with a matching event.

Standard JSON-RPC clients will reject the subsequent replies, as they announce a request ID (

x) that is already complete. This means a caller has to implement Tendermint-specific handling for these responses.Moreover, the result format is different between the initial confirmation and the subsequent responses. This means a caller has to implement special logic for decoding the first response versus the subsequent ones.

-

-

No way to detect data loss: The subscriber connection can be terminated for many reasons. Even ignoring ordinary network issues (e.g., packet loss):

-

The server will drop messages and/or close the websocket if its write buffer fills, or if the queue of undelivered matching events is not drained fast enough. The client has no way to discover that messages were dropped even if the connection remains open.

-

Either the client or the server may close the websocket if the websocket PING and PONG exchanges are not handled correctly, or frequently enough. Even if correctly implemented, this may fail if the system is under high load and cannot service those control messages in a timely manner.

When the connection is terminated, the server drops all the subscriptions for that client (as if it had called

unsubscribe_all). Even if the client reconnects, any events that were published during the period between the disconnect and re-connect and re-subscription will be silently lost, and the client has no way to discover that it missed some relevant messages. -

-

No way to replay old events: Even if a client knew it had missed some events (due to a disconnection, for example), the API provides no way for the client to "play back" events it may have missed.

-

Large response sizes: Some event data can be quite large, and there can be substantial duplication across items. The API allows the client to select which events are reported, but has no way to control which parts of a matching event it wishes to receive.

This can be costly on the server (which has to marshal those data into JSON), the network, and the client (which has to unmarshal the result and then pick through for the components that are relevant to it).

Besides being inefficient, this also contributes to some of the persistent connection issues mentioned above, e.g., filling up the websocket write buffer and forcing the server to queue potentially several copies of a large value in memory.

-

Client identity is tied to network address: The Tendermint event API identifies each subscriber by a (Client ID, Query) pair. In the RPC service, the query is provided by the client, but the client ID is set to the TCP address of the client (typically "host:port" or "ip:port").

This means that even if the server did not drop subscriptions immediately when the websocket connection is closed, a client may not be able to reattach to its existing subscription. Dialing a new connection is likely to result in a different port (and, depending on their own proxy setup, possibly a different public IP).

In isolation, this problem would be easy to work around with a new subscription parameter, but it would require several other changes to the handling of event subscriptions for that workaround to become useful.

Decision

To address the described problems, we will:

-

Introduce a new API for event subscription to the Tendermint RPC service. The proposed API is described in Detailed Design below.

-

This new API will target the Tendermint v0.36 release, during which the current ("streaming") API will remain available as-is, but deprecated.

-

The streaming API will be entirely removed in release v0.37, which will require all users of event subscription to switch to the new API.

Point for discussion: Given that ABCI++ and PBTS are the main priorities for v0.36, it would be fine to slip the first phase of this work to v0.37. Unless there is a time problem, however, the proposed design does not disrupt the work on ABCI++ or PBTS, and will not increase the scope of breaking changes. Therefore the plan is to begin in v0.36 and slip only if necessary.

Detailed Design

Design Goals

Specific goals of this design include:

-

Remove the need for a persistent connection to each subscription client. Subscribers should use the same HTTP request flow for event subscription requests as for other RPC calls.

-

The server retains minimal state (possibly none) per-subscriber. In particular:

- The server does not buffer unconsumed writes nor queue undelivered events on a per-client basis.

- A client that stalls or goes idle does not cost the server any resources.

- Any event data that is buffered or stored is shared among all subscribers, and is not duplicated per client.

-

Slow clients have no impact (or minimal impact) on the rate of progress of the consensus algorithm, beyond the ambient overhead of servicing individual RPC requests.

-

Clients can tell when they have missed events matching their subscription, within some reasonable (configurable) window of time, and can "replay" events within that window to catch up.

-

Nice to have: It should be easy to use the event subscription API from existing standard tools and libraries, including command-line use for testing and experimentation.

Definitions

-

The event stream of a node is a single, time-ordered, heterogeneous stream of event items.

-

Each event item comprises an event datum (for example, block header metadata for a new-block event), and zero or more optional events.

-

An event means the ABCI

Eventdata type, which comprises a string type and zero or more string key-value event attributes.The use of the new terms "event item" and "event datum" is to avert confusion between the values that are published to the event bus (what we call here "event items") and the ABCI

Eventdata type. -

The node assigns each event item a unique identifier string called a cursor. A cursor must be unique among all events published by a single node, but it is not required to be unique globally across nodes.

Cursors are time-ordered so that given event items A and B, if A was published before B, then cursor(A) < cursor(B) in lexicographic order.

A minimum viable cursor implementation is a tuple consisting of a timestamp and a sequence number (e.g.,

16CCC798FB5F4670-0123). However, it may also be useful to append basic type information to a cursor, to allow efficient filtering (e.g.,16CCC87E91869050-0091:BeginBlock).The initial implementation will use the minimum viable format.

Discussion

The node maintains an event log, a shared ordered record of the events published to its event bus within an operator-configurable time window. The initial implementation will store the event log in-memory, and the operator will be given two per-node configuration settings. Note, these names are provisional:

-

[rpc] event-log-window-size: A duration before the latest published event, during which the node will retain event items published. Setting this value to zero disables event subscription. -

[rpc] event-log-max-items: A maximum number of event items that the node will retain within the time window. If the number of items exceeds this value, the node discardes the oldest items in the window. Setting this value to zero means that no limit is imposed on the number of items.

The node will retain all events within the time window, provided they do not exceed the maximum number. These config parameters allow the operator to loosely regulate how much memory and storage the node allocates to the event log. The client can use the server reply to tell whether the events it wants are still available from the event log.

The event log is shared among all subscribers to the node.

Discussion point: Should events persist across node restarts?

The current event API does not persist events across restarts, so this new design does not either. Note, however, that we may "spill" older event data to disk as a way of controlling memory use. Such usage is ephemeral, however, and does not need to be tracked as node data (e.g., it could be temp files).

Query API

To retrieve event data, the client will call the (new) RPC method events.

The parameters of this method will correspond to the following Go types:

type EventParams struct {

// Optional filter spec. If nil or empty, all items are eligible.

Filter *Filter `json:"filter"`

// The maximum number of eligible results to return.

// If zero or negative, the server will report a default number.

MaxResults int `json:"max_results"`

// Return only items after this cursor. If empty, the limit is just

// before the the beginning of the event log.

After string `json:"after"`

// Return only items before this cursor. If empty, the limit is just

// after the head of the event log.

Before string `json:"before"`

// Wait for up to this long for events to be available.

WaitTime time.Duration `json:"wait_time"`

}

type Filter struct {

Query string `json:"query"`

}

Discussion point: The initial implementation will not cache filter queries for the client. If this turns out to be a performance issue in production, the service can keep a small shared cache of compiled queries. Given the improvements from #7319 et seq., this should not be necessary.

Discussion point: For the initial implementation, the new API will use the existing query language as-is. Future work may extend the Filter message with a more structured and/or expressive query surface, but that is beyond the scope of this design.

The semantics of the request are as follows: An item in the event log is eligible for a query if:

- It is newer than the

aftercursor (if set). - It is older than the

beforecursor (if set). - It matches the filter (if set).

Among the eligible items in the log, the server returns up to max_results of

the newest items, in reverse order of cursor. If max_results is unset the

server chooses a number to return, and will cap max_results at a sensible

limit.

The wait_time parameter is used to effect polling. If before is empty and

no items are available, the server will wait for up to wait_time for matching

items to arrive at the head of the log. If wait_time is zero or negative, the

server will wait for a default (positive) interval.

If before non-empty, wait_time is ignored: new results are only added to

the head of the log, so there is no need to wait. This allows the client to

poll for new data, and "page" backward through matching event items. This is

discussed in more detail below.

The server will set a sensible cap on the maximum wait_time, overriding

client-requested intervals longer than that.

A successful reply from the events request corresponds to the following Go

types:

type EventReply struct {

// The items matching the request parameters, from newest

// to oldest, if any were available within the timeout.

Items []*EventItem `json:"items"`

// This is true if there is at least one older matching item

// available in the log that was not returned.

More bool `json:"more"`

// The cursor of the oldest item in the log at the time of this reply,

// or "" if the log is empty.

Oldest string `json:"oldest"`

// The cursor of the newest item in the log at the time of this reply,

// or "" if the log is empty.

Newest string `json:"newest"`

}

type EventItem struct {

// The cursor of this item.

Cursor string `json:"cursor"`

// The encoded event data for this item.

// The type identifies the structure of the value.

Data struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

Value json.RawMessage `json:"value"`

} `json:"data"`

}

The oldest and newest fields of the reply report the cursors of the oldest

and newest items (of any kind) recorded in the event log at the time of the

reply, or are "" if the log is empty.

The data field contains the type-specific event datum. The datum carries any

ABCI events that may have been defined.

Discussion point: Based on issue #7273, I did not include a separate field in the response for the ABCI events, since it duplicates data already stored elsewhere in the event data.

The semantics of the reply are as follows:

-

If

itemsis non-empty:-

Items are ordered from newest to oldest.

-

If

moreis true, there is at least one additional, older item in the event log that was not returned (in excess ofmax_results).In this case the client can fetch the next page by setting

beforein a new request, to the cursor of the oldest item fetched (i.e., the last one initems). -

Otherwise (if

moreis false), all the matching results have been reported (pagination is complete). -

The first element of

itemsidentifies the newest item considered. Subsequent poll requests can setafterto this cursor to skip items that were already retrieved.

-

-

If

itemsis empty:-

If the

beforewas set in the request, there are no further eligible items for this query in the log (pagination is complete).This is just a safety case; the client can detect this without issuing another call by consulting the

morefield of the previous reply. -

If the

beforewas empty in the request, no eligible items were available before thewait_timeexpired. The client may poll again to wait for more event items.

-

A client can store cursor values to detect data loss and to recover from crashes and connectivity issues:

-

After a crash, the client requests events after the newest cursor it has seen. If the reply indicates that cursor is no longer in range, the client may (conservatively) conclude some event data may have been lost.

-

On the other hand, if it is in range, the client can then page back through the results that it missed, and then resume polling. As long as its recovery cursor does not age out before it finishes, the client can be sure it has all the relevant results.

Other Notes

-

The new API supports two general "modes" of operation:

-

In ordinary operation, clients will long-poll the head of the event log for new events matching their criteria (by setting a

wait_timeand nobefore). -

If there are more events than the client requested, or if the client needs to to read older events to recover from a stall or crash, clients will page backward through the event log (by setting

beforeandafter).

-

-

While the new API requires explicit polling by the client, it makes better use of the node's existing HTTP infrastructure (e.g., connection pools). Moreover, the direct implementation is easier to use from standard tools and client libraries for HTTP and JSON-RPC.

Explicit polling does shift the burden of timeliness to the client. That is arguably preferable, however, given that the RPC service is ancillary to the node's primary goal, viz., consensus. The details of polling can be easily hidden from client applications with simple libraries.

-

The format of a cursor is considered opaque to the client. Clients must not parse cursor values, but they may rely on their ordering properties.

-

To maintain the event log, the server must prune items outside the time window and in excess of the item limit.

The initial implementation will do this by checking the tail of the event log after each new item is published. If the number of items in the log exceeds the item limit, it will delete oldest items until the log is under the limit; then discard any older than the time window before the latest.

To minimize coordination interference between the publisher (the event bus) and the subcribers (the

eventsservice handlers), the event log will be stored as a persistent linear queue with shared structure (a cons list). A single reader-writer mutex will guard the "head" of the queue where new items are published:-

To publish a new item, the publisher acquires the write lock, conses a new item to the front of the existing queue, and replaces the head pointer with the new item.

-

To scan the queue, a reader acquires the read lock, captures the head pointer, and then releases the lock. The rest of its request can be served without holding a lock, since the queue structure will not change.

When a reader wants to wait, it will yield the lock and wait on a condition that is signaled when the publisher swings the pointer.

-

To prune the queue, the publisher (who is the sole writer) will track the queue length and the age of the oldest item separately. When the length and or age exceed the configured bounds, it will construct a new queue spine on the same items, discarding out-of-band values.

Pruning can be done while the publisher already holds the write lock, or could be done outside the lock entirely: Once the new queue is constructed, the lock can be re-acquired to swing the pointer. This costs some extra allocations for the cons cells, but avoids duplicating any event items. The pruning step is a simple linear scan down the first (up to) max-items elements of the queue, to find the breakpoint of age and length.

Moreover, the publisher can amortize the cost of pruning by item count, if necessary, by pruning length "more aggressively" than the configuration requires (e.g., reducing to 3/4 of the maximum rather than 1/1).

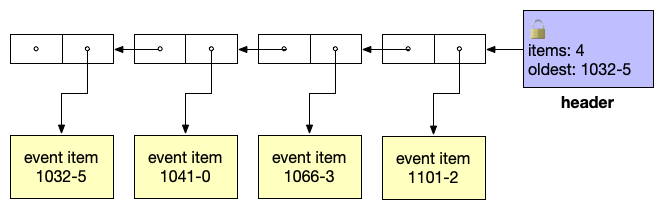

The state of the event log before the publisher acquires the lock:

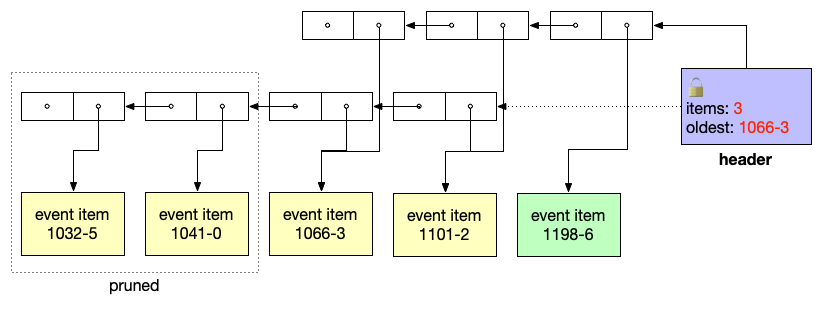

After the publisher has added a new item and pruned old ones:

-

Migration Plan

This design requires that clients eventually migrate to the new event subscription API, but provides a full release cycle with both APIs in place to make this burden more tractable. The migration strategy is broadly:

Phase 1: Release v0.36.

- Implement the new

eventsendpoint, keeping the existing methods as they are. - Update the Go clients to support the new

eventsendpoint, and handle polling. - Update the old endpoints to log annoyingly about their own deprecation.

- Write tutorials about how to migrate client usage.

At or shortly after release, we should proactively update the Cosmos SDK to use the new API, to remove a disincentive to upgrading.

Phase 2: Release v0.37

- During development, we should actively seek out any existing users of the streaming event subscription API and help them migrate.

- Possibly also: Spend some time writing clients for JS, Rust, et al.

- Release: Delete the old implementation and all the websocket support code.

Discussion point: Even though the plan is to keep the existing service, we might take the opportunity to restrict the websocket endpoint to only the event streaming service, removing the other endpoints. To minimize the disruption for users in the v0.36 cycle, I have decided not to do this for the first phase.

If we wind up pushing this design into v0.37, however, we should re-evaulate this partial turn-down of the websocket.

Future Work

-

This design does not immediately address the problem of allowing the client to control which data are reported back for event items. That concern is deferred to future work. However, it would be straightforward to extend the filter and/or the request parameters to allow more control.

-

The node currently stores a subset of event data (specifically the block and transaction events) for use in reindexing. While these data are redundant with the event log described in this document, they are not sufficient to cover event subscription, as they omit other event types.

In the future we should investigate consolidating or removing event data from the state store entirely. For now this issue is out of scope for purposes of updating the RPC API. We may be able to piggyback on the database unification plans (see RFC 001) to store the event log separately, so its pruning policy does not need to be tied to the block and state stores.

-

This design reuses the existing filter query language from the old API. In the future we may want to use a more structured and/or expressive query. The Filter object can be extended with more fields as needed to support this.

-

Some users have trouble communicating with the RPC service because of configuration problems like improperly-set CORS policies. While this design does not address those issues directly, we might want to revisit how we set policies in the RPC service to make it less susceptible to confusing errors caused by misconfiguration.

Consequences

- ✅ Reduces the number of transport options for RPC. Supports RFC 002.

- ️✅ Removes the primary non-standard use of JSON-RPC.

- ⛔️ Forces clients to migrate to a different API (eventually).

- ↕️ API requires clients to poll, but this reduces client state on the server.

- ↕️ We have to maintain both implementations for a whole release, but this gives clients time to migrate.

Alternative Approaches

The following alternative approaches were considered:

-

Leave it alone. Since existing tools mostly already work with the API as it stands today, we could leave it alone and do our best to improve its performance and reliability.

Based on many issues reported by users and node operators (e.g., #3380, #6439, #6729, #7247), the problems described here affect even the existing use that works. Investing further incremental effort in the existing API is unlikely to address these issues.

-

Design a better streaming API. Instead of polling, we might try to design a better "streaming" API for event subscription.

A significant advantage of switching away from streaming is to remove the need for persistent connections between the node and subscribers. A new streaming protocol design would lose that advantage, and would still need a way to let clients recover and replay.

This approach might look better if we decided to use a different protocol for event subscription, say gRPC instead of JSON-RPC. That choice, however, would be just as breaking for existing clients, for marginal benefit. Moreover, this option increases both the complexity and the resource cost on the node implementation.

Given that resource consumption and complexity are important considerations, this option was not chosen.

-

Defer to an external event broker. We might remove the entire event subscription infrastructure from the node, and define an optional interface to allow the node to publish all its events to an external event broker, such as Apache Kafka.

This has the advantage of greatly simplifying the node, but at a great cost to the node operator: To enable event subscription in this design, the operator has to stand up and maintain a separate process in communion with the node, and configuration changes would have to be coordinated across both.

Moreover, this approach would be highly disruptive to existing client use, and migration would probably require switching to third-party libraries. Despite the potential benefits for the node itself, the costs to operators and clients seems too large for this to be the best option.

Publishing to an external event broker might be a worthwhile future project, if there is any demand for it. That decision is out of scope for this design, as it interacts with the design of the indexer as well.

References

- RFC 006: Event Subscription

- Tendermint RPC service

- Event query grammar

- RFC 6455: The WebSocket protocol

- JSON-RPC 2.0 Specification

- Nginx proxy server

- FastCGI

- RFC 001: Storage Engines & Database Layer

- RFC 002: Interprocess Communication in Tendermint

- Issues:

- rpc/client: test that client resubscribes upon disconnect (#3380)

- Too high memory usage when creating many events subscriptions (#6439)

- Tendermint emits events faster than clients can pull them (#6729)

- indexer: unbuffered event subscription slow down the consensus (#7247)

- rpc: remove duplication of events when querying (#7273)